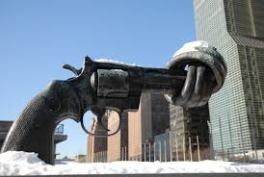

A Farewell to Arms: Comprehensive, International Arms Regulation Needed to Keep Weapons out of War Criminals’ Hands

By Stephen Lamony

The persistent ability of supposedly isolated dictatorships and armed groups to access weaponry demonstrates the degree to which international trade affects conflict, crime and human rights violations. Arms manufacturers’ role in enabling acts of aggression and atrocities has been recognized in international criminal law since the international military trials at Nuremberg, but has nevertheless survived effective regulation, undermining the possibility of a preventive approach to justice. Armories sustain and intensify conflicts and make armed groups more resilient to compromise and peacemaking efforts. There have been initiatives at the national, regional and international levels to prevent illicit arms trade, including regulations, treaties and embargoes. However, the measures deployed thus far have been ad hoc and have fallen short of the authoritative action required in order to counter a phenomenon so pervasive and large in scale.

The persistent ability of supposedly isolated dictatorships and armed groups to access weaponry demonstrates the degree to which international trade affects conflict, crime and human rights violations. Arms manufacturers’ role in enabling acts of aggression and atrocities has been recognized in international criminal law since the international military trials at Nuremberg, but has nevertheless survived effective regulation, undermining the possibility of a preventive approach to justice. Armories sustain and intensify conflicts and make armed groups more resilient to compromise and peacemaking efforts. There have been initiatives at the national, regional and international levels to prevent illicit arms trade, including regulations, treaties and embargoes. However, the measures deployed thus far have been ad hoc and have fallen short of the authoritative action required in order to counter a phenomenon so pervasive and large in scale.

Arms can and do play a specific and legitimate role in society. Chapter VII of the United Nations (UN) Charter makes provision for recourse to armed action in response to any threat to the peace, breach of the peace or act of aggression where the Security Council considers such action necessary. The inherent right to self-defense may allow for a resort to arms to ensure the life, liberty and physical integrity of a state’s citizens, as well as to protect the territorial integrity of the state against external military action. The responsibility of states to maintain civil order and social protection from internal threats may also necessitate the use of armed force. However, while legitimate arms trade cannot be eliminated, shadowy networks of renegade governments and unscrupulous war profiteers too easily manipulate favorable legal norms to ensure the proliferation of arms to areas where they are used to commit serious human rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law.

The 20th century has witnessed great changes regarding the issue of arms trafficking, with conventional weapons used in armed conflict now subject to the limitations of international humanitarian law. Still, the extent and type of weaponry currently available to states, as well as to terrorists, insurgents and other criminals is vast. Supply channels have been exploited and developed to traffic arms worldwide. Easy access to weaponry is facilitated through covert transfers by governments and commercial dealer black-market sales. In this epoch of globalization, in which international treaties have reduced regulatory impediments to transnational commerce, worldwide economic transactions have outgrown the ability of our multilateral institutions to regulate and police the economic dimensions of human rights abuses and armed conflict. A complex issue involving many actors, arms trafficking requires a concerted effort to find a solution aimed at obligating states to stop the flow of such supplies around the globe.

The UN, in its treatment of the arms trade, has tended to concern itself mostly with the non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. It has sponsored a number of multilateral non-proliferation instruments such as the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the Chemical Weapons Treaty and the Biological Weapons Convention. However, the carnage wrought by conventional arms in the civil wars of the 1990s exposed the UN’s failure to regulate and police the transfer of conventional weapons, which are now considered to be the real weapons of mass destruction. With the exception of a very limited number of conventional weapons that are deemed to have an excessively injurious or indiscriminate effect, the UN has failed to provide any effective regulations for the production, transfer and use of small arms. In the past, the UN had relied largely upon non-binding requests to national governments to create effective licensing standards to prevent the illicit transfer of small arms and to promote transparency. These watered-down consensus documents are concerned with the illicit transfer of arms and ignore the dangers that precipitate from state-authorized transfers.

It has been suggested that there is an emerging rule of customary law requiring states to refrain from exporting arms or authorizing the export of arms where they will be used in violation of the principles of international law or for the commission of human rights abuses. The Code of Conduct for Arms Exports adopted by the Council of the European Union in 1998, for example, articulates standards for any arms deal. Before authorizing any sale of small arms, the member state must first ensure that the purchasing state satisfies the criteria set down in the Code of Conduct. But such measures are widely considered to have “fallen woefully short of the mark”. They are non-binding and rely on the integrity of the signature states. Additionally, they are often disregarded in practice. It therefore seems farfetched to suggest that these measures amount to a customary rule of international law.

UN arms embargoes provide the only instance in which a sale of arms to specific countries is forbidden under international law. All UN member states are obliged to implement and monitor mandatory UN arms embargoes, but these count for little in reality as there tends to be no consequences for their violation. The Security Council or General Assembly resolutions that enact such embargoes do not declare that their violation constitutes a criminal offense, and in general there seems to be little more than a political responsibility to abide by these non-binding sanctions.

Fortunately, UN member states shook off their reluctance to impose efficient arms control measures when, in 2006, the UN General Assembly voted to take positive steps toward the creation an Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). This treaty was subsequently adopted on 2 April 2013, and represents a significant advancement in the regulation of international trade in conventional arms. At the time of writing, the ATT has been signed by 115 states and ratified by nine. Its full impact remains to be seen, but the landmark treaty contains strong human rights and international humanitarian law criteria which should serve to save lives and hinder the destabilizing flow of arms to conflict regions.

The manufacturers of arms and ammunitions may not be directly responsible for the atrocities committed with their wares, but they do play an important, if indirect role by supplying deadly weapons that often end up in the hands of some of the world’s worst human rights offenders. If the flow of arms to such criminals is to be stemmed, or even merely reduced, the world will need to back comprehensive, international efforts like the ATT.

Stephen Lamony is a Senior Adviser at the Coalition for the International Criminal Court. The views expressed here are his and do not reflect the official position of the CICC.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks